Across 35 states, there are 574 federally recognized American Indian Tribes and Alaska Native entities — each with its own language, traditions, history, and hard-fought journeys to recognition. Many other Tribes are recognized by their states or are still working toward federal acknowledgment.

Being federally recognized means the U.S. government formally acknowledges a Tribe as a sovereign nation — one with the right to govern itself, make and enforce laws, and engage with the federal government on a nation-to-nation level. It also means access to programs, funding, and resources that support Tribal housing, health, education, and self-determination.

Our Native American Programs Director, Jeff Ackley, knows this journey firsthand. A proud member of the Sokaogon Chippewa Community in Wisconsin — also known as the “Lost Tribe” — Ackley shares his family’s decades-long fight for recognition and the enduring strength of a community reclaiming its story, its land, and its future.

Boozhoo (Hello in Ojibwe),

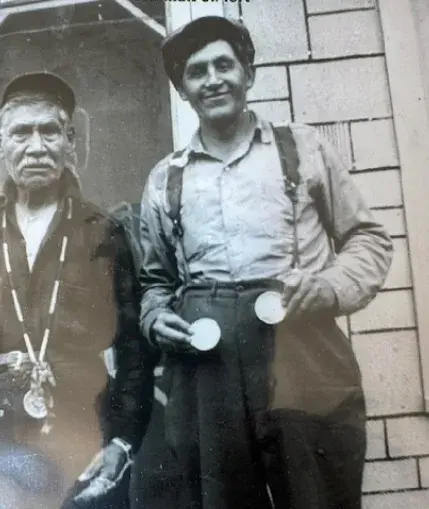

I am an enrolled member of the Sokaogon Chippewa Tribe of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians and the great-grandson of Chief Willard L. Ackley, the last hereditary Chief (Ogema) of our Tribal community.

Each autumn as the leaves change, the Sokaogon Chippewa people return to Rice Lake — one of Wisconsin’s few remaining ancient wild rice beds — to harvest Manoomin, the “food that grows on water.” This sacred tradition has been passed down for centuries, unchanged since our ancestors followed a prophecy that led them from eastern Canada to Madeline Island and eventually to this land rich in wild rice.

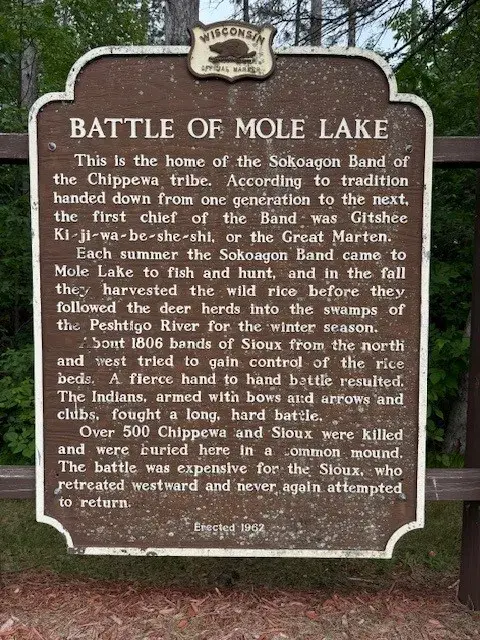

Our history is marked by both perseverance and loss. In 1806, the Battle of Mole Lake claimed more than 500 lives in fierce hand-to-hand combat with the Sioux. Later, our Tribe became known as the “Lost Tribe” after the legal title to our 12-mile-square reservation — granted under the 1854 treaty — was lost in a shipwreck on Lake Superior. Under Chief Willard Ackley’s leadership, and through generations of advocacy, the Tribe finally regained federal recognition and reservation status in 1937.

Today, the Sokaogon (Mole Lake) Chippewa Community is home to three beautiful lakes —Mole Lake, Bishop Lake, and Rice Lake — at the headwaters of the Wolf River. Our name, “Sokaogon,” or “Post in the Lake” people, honors a spiritually significant post that once stood in nearby Post Lake.

Chief Ackley, born in 1889 in a traditional wigwam on Bishop Lake, was revered as a spiritual leader, healer, and teacher of Ojibwe lifeways. As his nephew Fred Ackley Jr. shared, “He was chosen by the people the old way — he came to us down through heaven, through the sky, and was put here as an Ogema.” Chief Ackley devoted his life to preserving our culture and securing the Mole Lake reservation for future generations.

As his great-grandson, I carry forward his mission. We continue to seek the “lost treaty” that once promised our land — honoring the past to ensure the sustainability and self-sufficiency of generations to come.

Mii-gweech (Thank you),

Negonabenase (Spirit name: “Leading Bird”)

Jeff Ackley Jr.