Four days after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, Kwamé Juakali was walking with his family along the Interstate highway toward the Superdome, seeking shelter, food, and water. Juakali was 15 at the time and recalls coming across two older men in a car who were begging for water. “As exhausted and mentally drained as we were, I realized we were in better shape than a lot of people,” Juakali said. “But we didn’t have any water and couldn’t help these men. I remember knowing in my heart that these guys probably wouldn’t make it.”

Fast forward 20 years and Juakali has focused his career on rebuilding and reinforcing his native city, motivated in part by his conviction that “this kind of failed response should never happen again.”

While many New Orleans residents left their city and region after the unprecedented storm and never returned, Juakali and his family relocated temporarily to Memphis before coming home several months later. Juakali has devoted his life since then to his hometown, starting his career with AmeriCorps, then working for the city of New Orleans under Mayor Mitch Landrieu, and joining Enterprise in 2021.

We caught up with Juakali, program manager in Enterprise’s Gulf Coast office, to hear about his experience and to understand the impact and significance of Hurricane Katrina, 20 years later.

In his words:

Life in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina I was born and raised in New Orleans. My roots here run deep — my family moved from Mississippi and settled in the St. Bernard Housing Projects in the ’40s and ’50s. My parents met there; my mom worked at Head Start, and my dad was a community organizer. Right before Katrina, we were a family of five living in Section 8 housing in the St. Roch neighborhood. I have four sisters, and my mom was a single parent at that time.

We heard about the storm coming I was 15 and a sophomore in high school when Katrina came. Storms were routine, so when we heard about Katrina, we thought we would do the normal thing, which was to pack a three-day bag. We didn’t evacuate mainly because it was just too expensive. Instead, we went to my aunt’s apartment on the third floor of her house in the 7th ward, thinking we’d ride it out safely. We weren’t the only ones to have that idea and quickly there were 17 of us in a three-bedroom apartment.

When Hurricane Katrina hit At first, it didn’t feel unusual. But then the water started rising and soon we knew this wasn’t a regular storm. We stood on the balcony watching it cover the cars and creep into the lower floor apartments. The water was up to 10 feet, completely flooding the building’s first floor and then second floor. It was chaos. The families that were living downstairs came upstairs and it was extremely crowded.

After the storm By day two, we ran out of supplies. My mom was always a very resourceful person. She came up with the idea to drain the hot water heater for drinking water. On day three, it became clear that we had to rescue ourselves. There was a point where it felt like we might not make it out of there, because we had no food and water. Up until then, we thought there would be a national response and that we would be rescued. Then we realized that no one was coming and that we couldn’t stay there.

Rescuing Ourselves At a certain point, I remember looking down and seeing my sister’s boyfriend floating in a small aluminum boat. We used that boat to ferry our family to I-10 – it was our lifeline to reach higher ground. Some of us didn’t know how to swim, and I was one who did, so I was in the water for hours, swimming alongside, sometimes touching the tops of cars, pushing the boat from the house to the interstate. It took all day and night, trip after trip. But we got everyone to safety by nightfall. We slept on the interstate with hundreds of others, exhausted and scared.

The trip out of New Orleans The next day, we walked to the Superdome. That walk… I’ll never forget it. The Superdome was packed and chaotic. No air conditioning, barely any food, no toilets. We slept on the 50-yard line and got water and MREs.

Eventually, buses came. No one told us where we would be going, but we all had to line up for a bus. We stood for 12 hours in the hot sun. It was chaotic — my sister got separated and ended up in Houston. The rest of us were sent to Dallas. We got clean clothes, showers, and some dignity back. We reunited in Memphis where we stayed for several months, and I went to high school there.

Homecoming In December 2005 we returned to New Orleans. Our house on the East Bank had too much roof damage so we couldn’t live there. We found housing on the West Bank, which hadn’t flooded as badly. That’s where I finished high school — at Perry Walker. I’d grown up an East Bank kid, so switching sides like that felt like a big deal in New Orleans.

Coming back was strange. A lot of my friends didn’t come back or came back much later. But my cousin and my godbrother returned too, so I had a small circle, a kind of anchor. It was like starting over. Again.

Changing career plans Before Katrina, I wanted to be an attorney like my dad. I played football since I was a kid. I was good, but I knew I didn’t have the size to go pro, so I thought I’d work in the field some other way, as a sports attorney. Everything changed for me when I saw those two men in the car during the evacuation. That moment stuck with me and it still does so many years later.

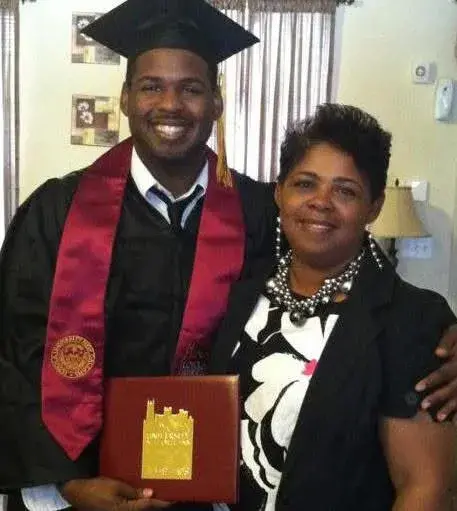

Even in college, I was prepping for law school. I took the LSAT twice. But halfway through my senior year, I had a crisis of conscience. None of it made sense anymore. I joined City Year through AmeriCorps, worked in a school in Gentilly, and it hit me: I didn’t want to be a lawyer. I wanted to make sure what happened to me didn’t happen to anyone else. That led me to policy and community advocacy. That experience was pivotal, and I’m still involved as a City Year New Orleans board member.

What home means Home is safety. It’s where I can be vulnerable. It’s the foundation of the community and a big part of who I am. Despite everything, I’m still here. I’ve dedicated my career to this city. I can’t imagine living anywhere else, as long as there’s still a New Orleans to live in. We have such deep roots in New Orleans. We really didn't know how to be at home anywhere else.

After 20 years, so much has changed. The population has shifted. Gentrification has reshaped neighborhoods like St. Roch. Families are being bused for hours to school. We lost a lot of our native community. Still, there’s beauty here. The new schools, libraries, infrastructure — they’re amazing. Some neighborhoods like Lafitte were rebuilt the right way, with community involvement. That matters.

New Orleans isn’t what it was before Katrina. But cities change. And as long as we keep fighting for it — keeping culture, people, and community at the center — we will hold onto what makes this place home.