In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, with a long and daunting road ahead, Gulf Coast states looked to the federal government for help. The first major lifeline from Washington would be the Gulf Opportunity Zone (GO Zone) Act of 2005.

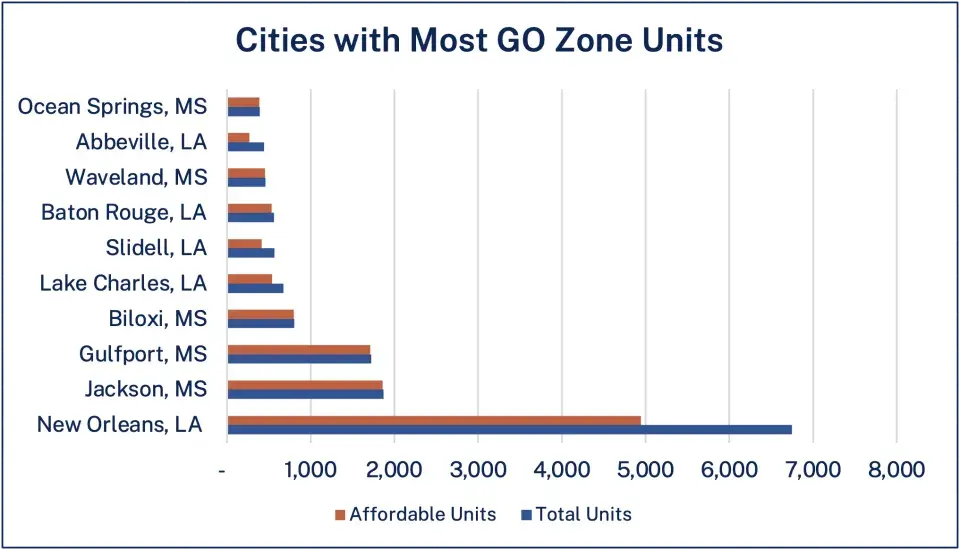

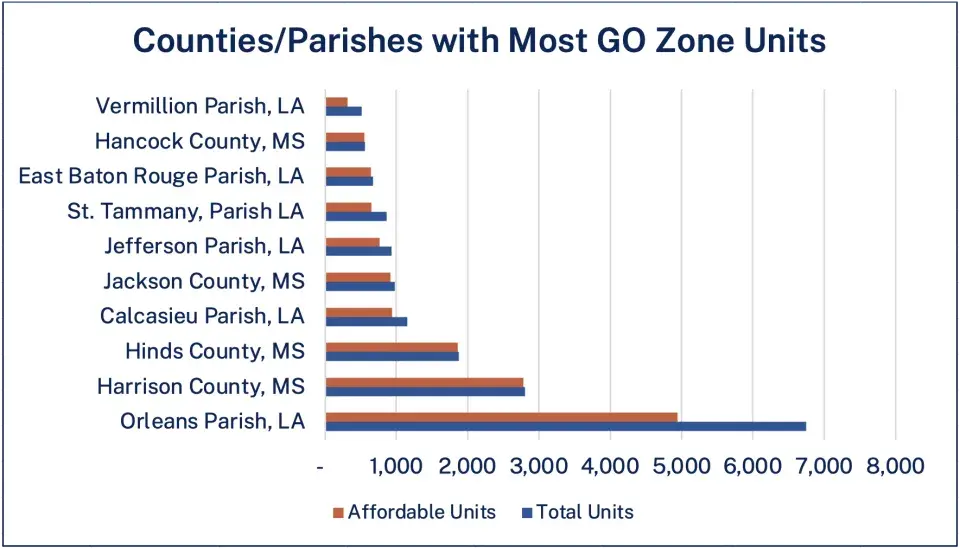

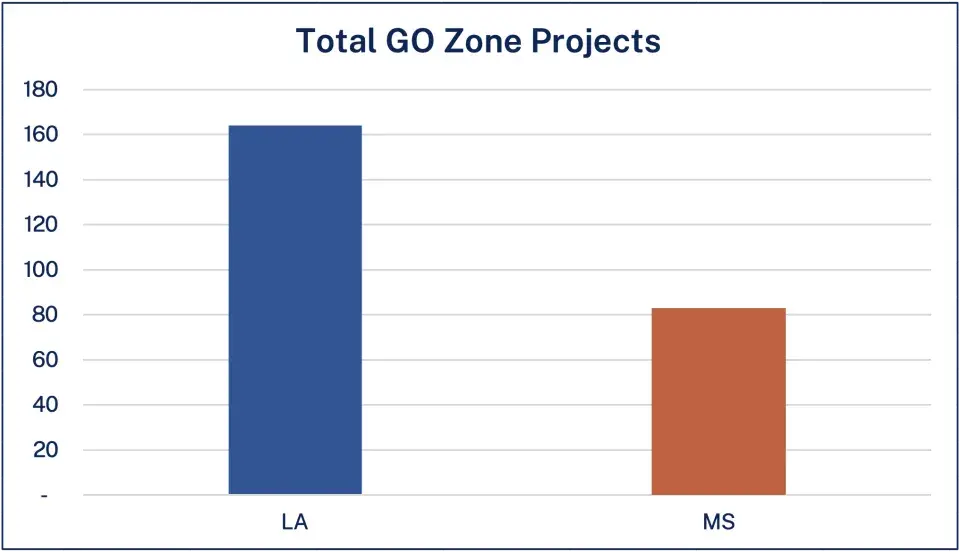

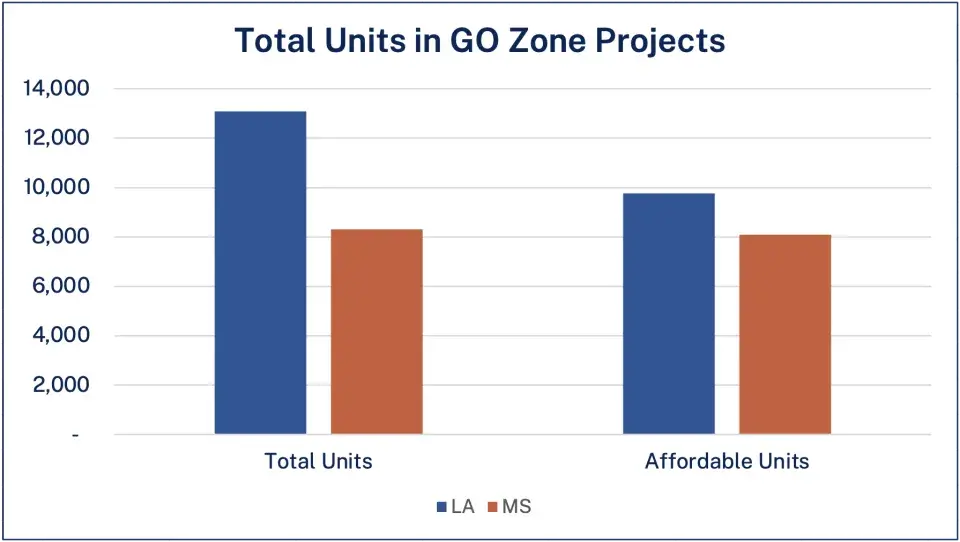

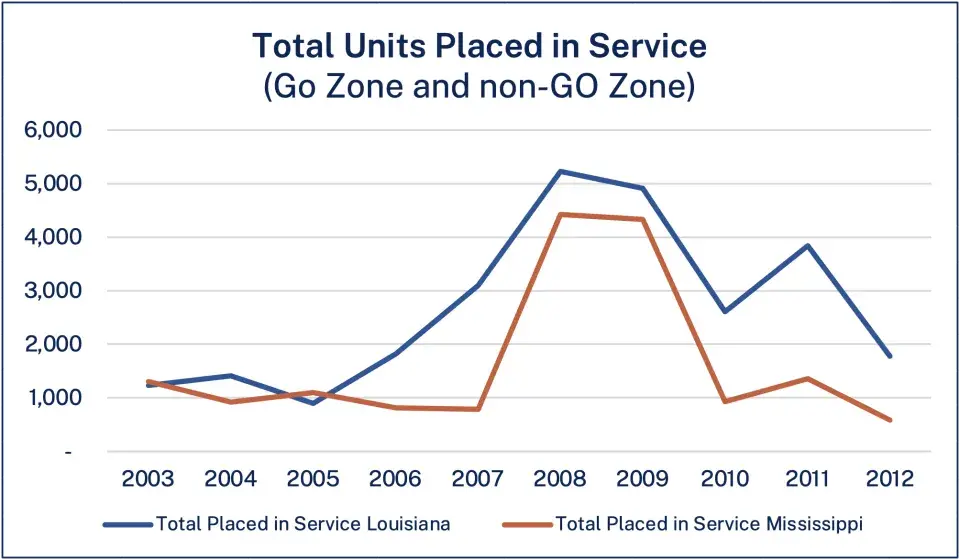

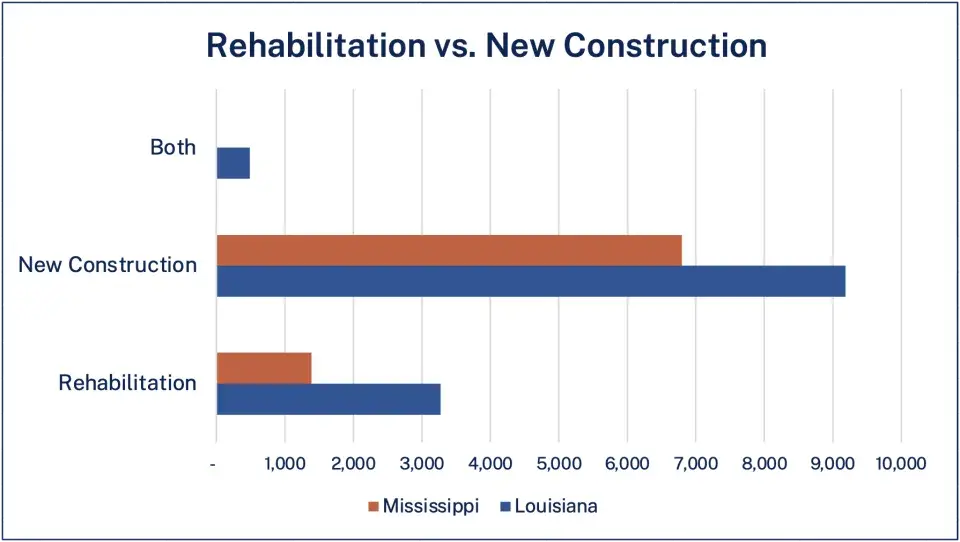

The legislation provided a big boost to rebuilding housing in part through supercharging the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (housing credit) and multiplying credit allocations to disaster areas. Although the process took longer than anyone wanted, the results – 13,000 new and rehabilitated homes in Louisiana and 8,300 in Mississippi – were a lifeline to residents looking to come back home.

Now, 20 years after Hurricane Katrina, it’s time for policymakers to turn their focus toward ensuring the long-term viability of these essential housing developments. Preserving these homes to keep them affordable and sustainable is a crucial part of that effort. Although preservation presents challenges, they can be overcome through consistent and dedicated action by policymakers.

Katrina, GO Zone, and the Housing Credit

The GO Zone Act was passed by Congress on December 16, 2005, three and a half months after the landfall of Hurricane Katrina. The legislation delivered tax incentives, changes, and allocation increases to leverage private commercial investment to rebuild businesses, manufacturers, health facilities, and commercial centers.

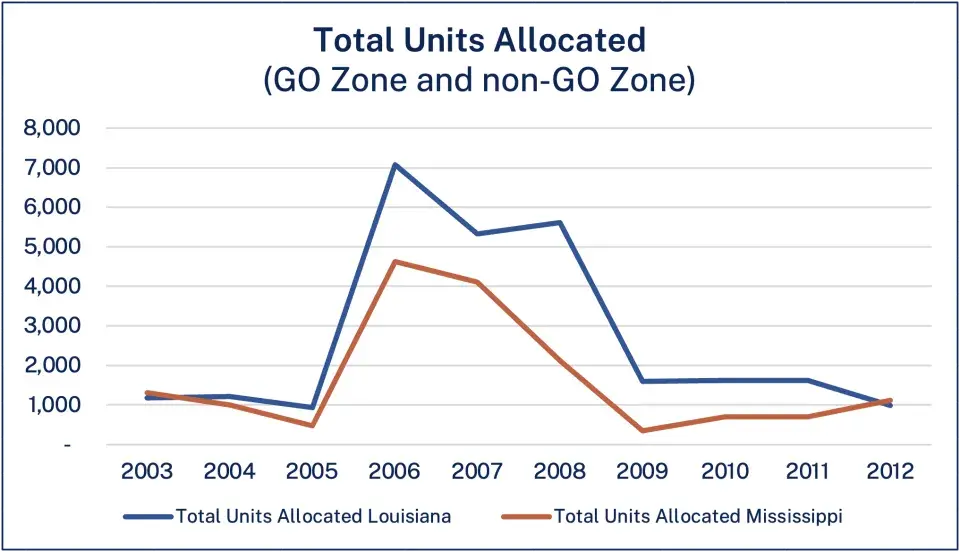

The GO Zone Act leveraged the housing credit’s role as the nation’s most successful tool for building and rehabilitating affordable rental housing by significantly increasing the allocation of credits to Katrina-impacted areas in 2006, 2007, and 2008.

A state’s housing credit allocation is determined by its population size. However, for the GO Zone – the counties and parishes designated as Katrina disaster areas where residents qualified for Federal Emergency Management Agency assistance – that allocation was increased by more than nine times.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, that resulted in Mississippi and Louisiana receiving more than six times the normal housing credit allocation from 2006-2008. Alabama would receive a 75 percent boost over that timeframe, and Texas and Florida would receive a one-time GO Zone allocation of $3.5 million.

Preserving GO Zone Homes

Preservation – ensuring an affordable home stays affordable and well maintained – is an important piece of a robust housing framework and should serve as a complementary strategy to constructing new homes. Preservation policies can target subsidized affordable housing as well as homes without any public subsidy or formal affordability requirements that are nonetheless affordable to low- and moderate-income residents.

Three aspects are key to preserving GO Zone properties.

Length of Affordability

Housing credit properties have minimum affordability periods of 30 years, and state housing finance agencies often mandate or incentivize longer periods. However, a loophole allows properties to remove affordability restrictions after 15 years through the Qualified Contract process. Enterprise strongly opposes this process and has advocated for its removal from both federal law and state program policies.

Our examination of GO Zone properties finds some risk of these early opt-outs in Mississippi but little risk in Louisiana. The Mississippi Home Corporation (MHC) incentivized 40-year affordability, and 25 of 36 Mississippi coastal properties Enterprise sampled have 40-year affordability terms, while eight, nearly 25%, have no long-term requirement.

In Louisiana, the Louisiana Housing Corporation (LHC), incentivized 25- to 35-year affordability periods and required 35-year affordability for properties using Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery funds. These provisions bound most of these properties to longer affordability.

Ongoing Physical Viability

Like other multifamily properties, housing credit properties maintain reserves to cover normal maintenance and upkeep needs, but, because of rent restrictions and tight underwriting standards, will not produce the profit needed for major renovations and upgrades during the long lifecycle of a building. For some GO Zone properties, those renovations and upgrades are needed now.

Generally, properties rehabilitated with GO Zone credits have the most need. A combination of the housing crisis created by the displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents and restrictive substantial rehabilitation rules necessitated that speed take precedence.

Substantial rehabilitation rules require a property to be fully brought up to code when rehabilitation costs exceed 50 percent of its fair market value, and significant repair costs along with low property values meant the 50 percent threshold was easily reached. Scopes of work were drafted to renovate and repair units as inexpensively and quickly as possible so families living in trailers, in hotels, or with family could come back home.

The current reality is that many properties now have very old systems. There are buildings that are 40 to 60 years old that have never had significant upgrades to air conditioning, heating, electrical, and other mechanical systems. These buildings will need major renovations soon to remain physically sustainable.

Resilience Upgrades

In addition to the renovations described above, these properties will need upgrades to improve energy-efficiency and withstand flooding, wind, and other climate impacts so they can remain viable over the long term (or even the short term).

Stronger building codes and higher elevations were incorporated after Katrina, but many resilience features common today were not created or widely used at that time. These include the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety’s FORTIFIED Home standard (now incentivized by both the MHC and LHC), and green infrastructure and other innovative floodwater management techniques. Ironically, Katrina inspired or accelerated many of these innovations but too late to be widely adapted during the recovery process.

Resilience is not just a physical need but an economic one. Increasing insurance costs due to climate effects are pushing property viability to the brink. The main solution identified to reduce insurance premiums are wind-resilient retrofits, namely incorporation of the FORTIFIED standard.

Solutions and Next Steps

Policymakers already have resources available at the state and local levels to start taking on the task of preservation if it is designated as a strategic priority. The affordable housing community should take proactive steps to identify at-risk properties and quantify capital repair needs.

Identifying At-Risk Properties and Quantifying Capital Repair Needs

Stakeholders can use Capital Needs Assessments (CNAs), comprehensive inspections that identify a property’s current and future repair and replacement needs along with estimated costs over a set period, and other data sources to estimate capital repair needs, estimate costs, and prioritize the most at-risk properties.

Designating or Prioritizing Public Resources for Capital Repairs

Preservation of these properties will require a combination of:

- Private debt financing

- Resyndication of Housing Credits: new allocations of 9% or 4% credits

- Soft funds, including HOME, Community Development Block Grants, and local Housing Trust Funds

- Bond proceeds

The most promising route may be pairing 4% housing credits and Private Activity Bonds (PABs) with a source of soft funds, like HOME or CDBG (and in New Orleans the newly enacted Housing Trust Fund). Using 4% housing credits was recently made easier with regulatory changes that make it simpler to qualify.

Conclusion

The GO Zone Act has proven successful in its mission of bringing back safe, affordable homes for many residents who lost their homes in Katrina and Rita. Those homes hold an invaluable place in their community’s housing ecosystem.

Now, housing policymakers and stakeholders must acknowledge the need to preserve those properties to sustain the GO Zone’s legacy of housing stability and affordability along the Gulf Coast.