It’s been 20 years since Enterprise created Green Communities – the nation’s only green building program designed with and for the affordable housing sector. Today, the program is baked into housing finance policies across 31 states and the District of Columbia, with close to 200,000 units certified, and hundreds of thousands of people living in affordable homes that are more efficient, resilient, and healthier for residents and the planet.

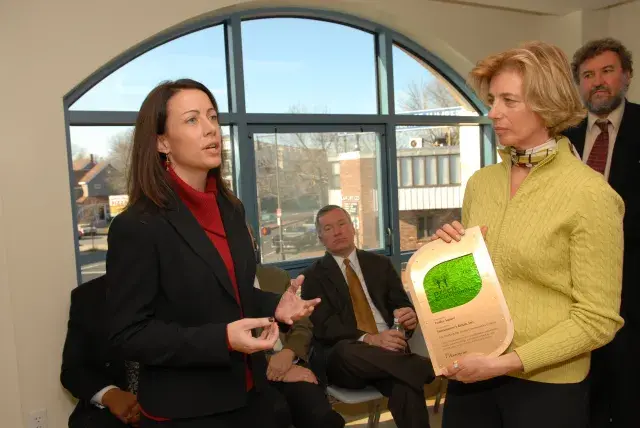

Dana Bourland, former vice president of green initiatives at Enterprise, was there from the beginning, when Green Communities was no more than a bold idea. Key among her contributions is a narrative shift, whereby affordable housing development begins with an integrated design process that draws multiple perspectives and considers how the entirety of a building can benefit people and the natural environment.

Bourland is the author of Gray to Green: A Call to Action on the Housing and Climate Crises and directed over $1 billion toward creating resilient communities while working in philanthropy. Today, her focus is on land-reunion efforts as co-founder and president of Soils & Vessels, which provides capital and resources to help reunite communities with their sacred and ancestral land. Bourland's wide-ranging accolades include Returned Peace Corps Volunteer, Ironman finisher, and Fast Company’s Most Influential Women in Technology.

Across these achievements, one constant remains: her visionary leadership to create a planet that is healthier and more equitable. As the national standard undergoes undergo a periodic refresh and Enterprise prepares to roll out the 2026 criteria, Bourland spoke about the launch of Green Communities and why it offers a blueprint for what’s next.

In 2004, you were instrumental to the creation of Green Communities. You said there was an appetite in affordable housing at the time to engage in green building. Did you face any challenges?

The biggest hurdle then and now is the mindset that speed and quantity are all that matter in affordable housing. The idea that “any housing is good housing” can make it hard to advance smarter, more future-proof approaches.

Low rent doesn’t mean much if housing is unhealthy, poorly located, or vulnerable to climate risks. If we ignore those realities, we risk doing more harm than good. Green Communities pushed the field to raise the bar so housing was delivering health, economic, and environmental benefits for all, including our planet and the people in communities where housing materials are manufactured.

The Green Communities criteria have evolved over the years and Enterprise is now updating them for 2026. What was the process of creating the first set of criteria?

When we launched, the idea was simple: advance an integrated design approach that recognized certain items as mandatory so that no matter what zip code someone lived in, they would get the same benefits.

Developers were meeting some criteria, but typically not all. For example, in colder places and where electricity was expensive, housing was generally energy efficient but the developer may have specified materials that were in the red zone, meaning they contained classes of toxic chemicals that can be harmful and potentially life-threatening to communities where they are manufactured, the workers installing them, and the residents regularly coming in contact with them through paint, flooring and insulation.

There is nothing better than talking to a person whose child wasn't woken up in the middle of the night because they couldn't breathe, or a family who no longer had to 'eat cheap' during utility bill week.

We backed up every mandatory item with cost data, technical assistance, and early grant and predevelopment funding. Over time, updates have become more targeted based on where developers are building and whether they are retrofitting housing.

The criteria have also become more responsive to climate science, health data, and building performance. But the principle is the same: lead with what works and make it practical and cost-effective to do the right thing.

You must have encountered some naysayers while working to launch the Green Communities standard. How did you handle that?

We didn’t dismiss resistance; we used it to provide better technical assistance and partner with trusted entities, particularly those with credible building science and public health expertise. And there’s nothing more persuasive than showing what’s possible. A walk through a Green Communities development, hearing from residents whose health has improved, or seeing the performance metrics – that’s what changes hearts and minds.

Some people had asthma and then did not have asthma triggers a day or two after moving into a Green Communities certified home. There is nothing better than talking to a person whose life was changed, whose child wasn’t woken up in the middle of the night because they couldn’t breathe, or a family who no longer had to “eat cheap" during utility bill week.

So it was important to show the naysayers evidence of how everyone and their bottom line benefit. Green development, after all, reduces risk for the developer, owner, operator, and the bank and investor. It future-proofs the building as it limits exposure to volatile energy prices and contributes to better health for residents, who are then less likely to miss work [or school]. And it makes the asset easier to maintain and operate, especially if it is generating and storing its own electricity through solar, wind, or geothermal.

Since leaving Enterprise in 2012, you worked at The JPB Foundation (now the Freedom Together Foundation), wrote a book, and recently co-founded a new organization. Yet Green Communities remains an industry standard – what does that mean to you?

It’s deeply satisfying and brings me joy. We set out to prove that affordable housing could lead the way, not lag on providing solutions to climate change, health disparities, and economic inequality. And that’s what happened, even though we still have more to do, particularly on equity and justice.

When the Inflation Reduction Act passed, the affordable housing sector had a seat at the table. They could say, “We’ve been building this way for years, and we’re ready to scale.” Green Communities laid the groundwork, and developers and owners showed it was possible.

Looking ahead, what do you see as the main challenges and opportunities for affordable housing?

The first hurdle is political will. We know how to end the housing crisis. We must treat housing as essential infrastructure designed for health, resilience, and equity. That means investing in deeply affordable green homes rooted in community, not speculation and profit. And it requires using the full power of the public purse to direct the resources and regulations needed to make it so.

The second is recognizing that the housing crisis and the climate crisis are two sides of the same coin. We can’t separate them. Every new home must be built to withstand heat, floods, storms, and power outages. One way to do that must be to put residents in the driver’s seat to inform what they need from their home and how they can benefit economically over the long term.

And we must reckon with history. Housing in this country has divided communities and exploited land. We need models rooted in ownership, sovereignty, and repair, where communities shape their future, not just survive it. We cannot make green communities at the expense of making other communities gray.

You’ve said that housing is about a lot more than four walls and a roof. What do you mean?

We have decades of data showing that low-income communities and communities of color are disproportionately burdened by pollution from industries that produce “gray” housing: cement, steel, gas, and highways. Neighborhoods are over-exposed to toxic chemicals, heat, and flooding, and under-protected by infrastructure, services, and policy.

But it’s not just about buildings, it’s about land. Gray housing is too often built on or near land that’s been contaminated, paved over, or stripped of natural defenses like trees and wetlands. These are the same lands that have been taken from Indigenous communities, rezoned in African-American neighborhoods, and devalued over generations.

If we reimagined how we use land – both for industries that make housing construction and home building possible, and by prioritizing ecological restoration, proximity to opportunity, and community stewardship – we could rewrite the legacy of harm. Green Communities offers a blueprint.

Vesna Jaksic Lowe is an award-winning journalist. Read more of her writing in our Resilient 7 series recognizing housing and community leaders building a more sustainable future.