Enterprise recently launched its new blog post series, Policy Actions for Racial Equity (PARE), to explore the many ways that housing policies contribute to racial disparities in our country. Before delving into current policies, however, we need to understand the historical context in which such policies are created and implemented. This includes exploring the legacy of racist housing policies and practices that established segregated neighborhoods, which continue to foster racial disparities in health, education, and economic systems.

This blog describes how more than 300 years of exploitive and racist housing policies fostered many of the socio-economic inequities currently borne by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC). It is necessarily brief and does not address every practice that federal, state, and local governments actively or passively used to disadvantage BIPOC. Yet even the few examples described below nonetheless reveal many of the ways that housing policies have historically and systemically enforced or facilitated racial segregation and marginalization.

Pre-20th Century Land and Housing Policies

Land ownership has always been restricted in the United States, even before it was an independent nation. Early European colonists claimed land from Native tribes and forced Native populations to live in designated districts separate from colonial settlements. As these settlements grew, colonial governments appropriated more territory from Native populations and limited their rights to own and sell property. In 1763 the British government offered some protection to Native lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, though following the American Revolution the new U.S. government invalidated the prior agreement and seized lands from Native tribes that had fought against the colonists.

Through the first half of the 19th century, as the United States continued its westward expansion and appropriation of even more Native lands, additional restrictions were placed on who could own property. Discrimination by race, as well as by religion and country of origin, was rampant, permitted by policies that either actively encouraged or did little to prevent it. In some states, free Black men were forbidden from purchasing land, and courts routinely invalidated gifts and other transfers of property to Black people. Even outside of slave-holding jurisdictions, opportunities for land ownership were often limited, either by direct law or the failure to regulate discriminatory practices against people of color.

Policies in the post-Civil War period continued to limit BIPOC property ownership. Prohibitions on Black land acquisitions increased following Emancipation in former slave-holding states, while exploitive practices like sharecropping entrenched existing racial power inequities. Elsewhere, socially, economically, and legally enforced residential segregation further prevented BIPOC from accessing housing and wealth-building opportunities. For example, Asian laborers brought to the U.S. in the late 19th century were often forced to live in ethnic enclaves and could not acquire property outside these designated districts, some of which evolved into the iconic Chinatown neighborhoods popular with tourists today.

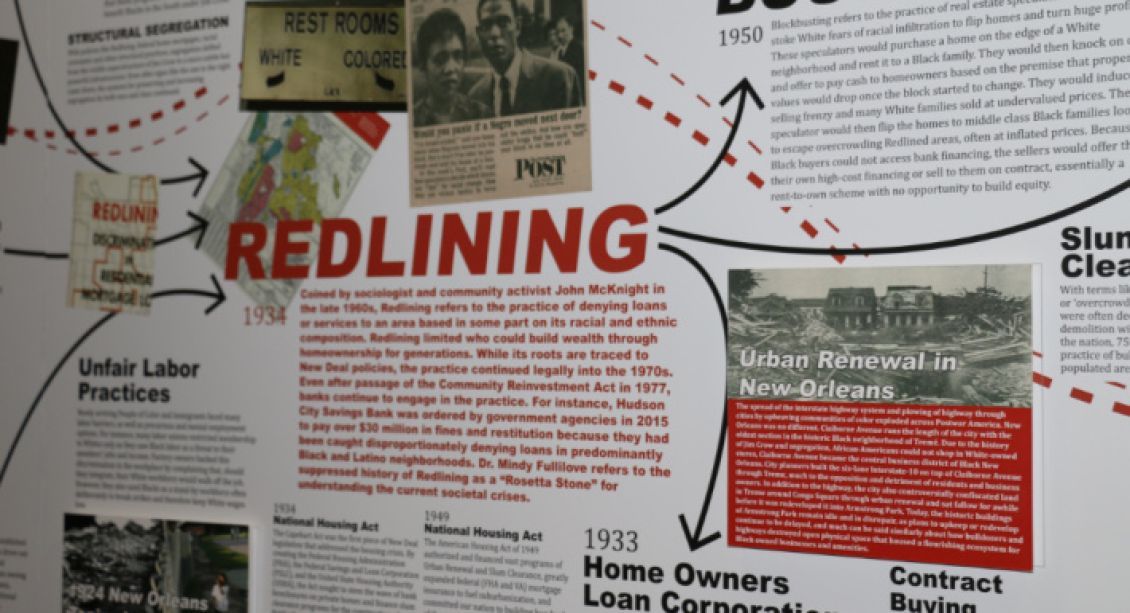

Segregated Neighborhoods and Redlining

Around the turn of the 20th century, a new wave of housing and land-use policies were introduced across the United States, to facilitate the dispersal of households from crowded cities and encourage more property ownership. Underlying many of these laws, however, was a concerted effort to segregate households by race and ethnicity. Some state and local policies were explicit in their exclusion of BIPOC from living and owning property in certain communities, arguing that integration would lead to social and civil unrest. Others segregated neighborhoods economically by permitting only single-family homes to be built in the most desirable neighborhoods, effectively pricing out most households of color from these areas. A lack of enforcement against private acts of overt discrimination – such as deed restrictions that prevented resale of individual properties to anyone of a designated race – further cemented residential segregation as the norm in housing markets.

The federal government was largely uninvolved in housing policy to this point in time, opting not to directly encourage or discourage segregation at the local level. This changed during the Great Depression when new federal programs were developed to help stimulate the economy through home building and buying. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created to lead this effort by insuring home mortgages, allowing banks to lend and households to purchase homes more securely and less expensively than ever before. To protect against value loss on insured properties, however, the FHA only covered loans on newly constructed housing in stable neighborhoods, as defined by color-coded maps developed by local real estate boards based on existing distributions of population and housing types – that is, racially segregated by local policy and private actions already in effect.

These industry groups routinely rated neighborhoods with large concentrations of Black households and other distinct racial/ethnic subgroups as being the least stable and outlined these in red, giving rise to the term ‘red-lining’ to describe the exclusion of most households of color from accessing low-cost mortgage credit and better quality housing. Red-lining continued through the post-World War II era, with FHA maps guiding not just mortgage insurance but also the securitization of loans by Fannie Mae and low-interest rate borrowing by veterans under the GI Bill.

The boom in white property ownership that resulted from these federal actions not only facilitated neighborhood segregation, but also gave white households access to an appreciable asset from which they could build wealth. Meanwhile, households of color, unable to benefit from most of these programs, became even further concentrated in neighborhoods with substandard housing, low appreciation, and a lack of public and private investment.

Public Housing and Urban Renewal

As the federal government further entrenched and expanded the suburban segregation that local policies had initially created, it also worked in urban areas to disadvantage communities of color. Publicly-built and subsidized rental housing, for example, provided a inexpensive housing option for low-income households, but designated most of the newer housing in nicer parts of the city as available to white families only, leaving low-income households of color isolated in neighborhoods with fewer jobs, worse schools, and greater exposure to environmental hazards.

Federal policies and funding were also instrumental in efforts by city governments to displace communities of color, to make room for new highways, commercial centers, and other ‘urban renewal’ efforts. The perception of poor urban neighborhoods as blighted – and their residents as disposable – justified their removal, even though in reality most were stable, tight-knit communities. The development of Lincoln Center in New York City, for example, forced the relocation of over 7,000 families and 800 businesses in a neighborhood with large Black, Puerto Rican, and Asian immigrant populations.

Funds paid out to property and business owners in these neighborhoods were generally insufficient to replicate what was lost, to say nothing of the community bonds severed in the process. A 1965 report confirmed the detrimental effects of these urban renewal projects, noting that most “non-whites have been forced into already crowded housing facilities, thereby spreading blight, aggravating ghettoes, and generally defeating the social purpose of urban renewal”.

Fair Housing Policy

Despite the 1968 federal Fair Housing Act making race-based housing discrimination illegal, disparate treatment of BIPOC in property and mortgage markets has continued over the last 50 years, through a combination of weak enforcement and regulation against discriminatory practices, and new policies built on the legacies of past inequities. The Fair Housing Act itself was passed with no mechanisms for either punishing perpetrators of housing discrimination, nor for providing relief to families negatively affected. Nor did the Act define what constituted a discriminatory act, giving license to housing industry agents to develop alternative ways to disadvantage families of color, such as through neighborhood steering and direct marketing.

The Fair Housing Act also provided no means to undo the damage of the prior two centuries of racist housing policies, leaving instead a status quo upon which all subsequent housing policies were applied. Local zoning policies, for example, often seek to enshrine existing neighborhood ‘character’ by limiting the types of housing that can be built, effectively preventing lower-cost developments that could open up predominantly white single-family neighborhoods to more families of color. The private mortgage market also operates within this system, which allows it to treat borrowers differently by offering higher cost and riskier loan products to those from certain neighborhoods or income levels. Since such activities are not predicated explicitly on race, however, policy options to prevent their disparate impacts on BIPOC are limited.

Other attempts at reconciling racial segregation have similarly produced mostly weak results. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), for example, sought to pressure lenders into serving communities of color through regulation and increased transparency of disparities in mortgage markets. Penalties against infractions of these policies, however, remain insufficient to preventing the perpetuation of existing racial inequities in homeownership.

The result of these failures of public policy to undo past discrimination is the extension of disparate housing outcomes for families of color, many of whom continue to live in segregated neighborhoods with less public and private investments, worse environmental conditions, and fewer prospects for advancement. Fewer BIPOC own their homes, and those that do have generally more expensive mortgages and lower house values relative to comparable white homeowners, which inhibits wealth accumulation and intergenerational transfers. To better advance racial equity, therefore, will require acknowledgment of the myriad ways public policies still contribute to residential segregation and racial discrimination in housing markets.

Take Action:

- Learn more about the history of housing discrimination and racist housing policies

- Check out the Undesign The Redline exhibit to understand the legacy of housing segregation

- Read about the effects of housing discrimination and the need for better Fair Housing enforcement

We encourage all who believe in creating a just society to read, discuss, and share the PARE blog series as we learn and act to address the impacts of housing policies on racial equity in America. We also invite you to join us in this conversation, by suggesting additional topics and sharing resources for how we can advocate for greater racial equity. If you’d like to offer feedback on our body of work, please reach out to the Public Policy team. You can also check out our blog for more information on Enterprise’s federal, state, and local policy advocacy and racial equity work.