My grandparents were part of the exodus of emigres into the United States from the Pale of Settlement, which was a term that referred to the region of Jewish communities or “shtetls” that stretched over the Ukraine, Russia, and Poland. Persecuted politically and restricted economically, thousands of Jews emigrated from the Pale to find opportunity in the United States. After leaving Odessa, Ukraine my grandparents traveled by ship to New York City’s Ellis Island. From there, half moved to Atlanta by train, and the other half into New York City, by foot. Both sets settled into communities that had been established by previous Jewish settlers, pioneers who welcomed my family and provided economic, social, and cultural support to establish their households and build their future. My grandparents and their children built stores and opportunities for my family and created jobs and energized the local economies they supported. Their role, like the millions of incoming families and households, have built our nation.

There is another type of migration that is projected to increase over the next century-households fleeing climate impacts and extremely climate vulnerable areas of the country. A battery of cascading impacts--including a warming planet and rising seas--threatens the current and future habitability of many coastal settlements across the globe, particularly communities with degraded infrastructure, insufficient housing stock and lack of financial reserves to quickly rebuild. Climate realities are creating more “tipping point” scenarios--the critical point in a situation or system beyond which a significant and often unstoppable effect or change takes place--than ever before. The tipping point moment shows up for many communities as a sudden and drastic event---a tsunami, a flood, a forest fire, or an earthquake. Lives are lost both in the initial shock and subsequent flight, particularly if there is nowhere safe for refugees to go. journeys1. With no adequate systems in place and limited receiver communities available, refugee camps have become permanent settlements, creating more trauma, more displacement, and more distress for settlers.

Creative Commons: Home destroyed by Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, Louisiana 2005

In 2019, weather-related disasters internally displaced more than 23 million people around the world2 estimated by Refugees International. The Urban institute states that in the US more than 1.2 million of those displaced were Americans. Adverse effects of global climate change induce more extreme weather, growing food insecurity, and rising sea levels—that number is expected to rise. Tragically, the communities most impacted by climate impacts and risks are communities that have less financial reserve, are less able to rebuild in their community and become literally “stranded” and forced to search for higher ground. Forced to adapt, households often move to big cities in search of stability. However, poor, and untenured housing conditions, the absence of social protection like medical insurance and inadequate resources or any financial bridge support often mean they are no safer from nature’s fury in the city3 than they were before leaving home. Leaving home and uprooting one’s life is risky. Change on such a large scale is never easy, for immigrants or for the communities into which they settle, which are commonly called “receiving communities.”

The numbers of internally displaced households will escalate alongside the rise in fire, flood, and other natural perils. US cities and communities must prepare better to receive communities that have been displaced by natural and human hazards alike. For my grandparents, the ability to migrate to a community that was accepting, supportive and adaptive was critical to their survival, and in turn they contributed economically, socially, and culturally to their new home. Every household displaced by a live threatening shock or stress should have the opportunity that was afforded to my grandparents.

Preparing Receiving Communities

It’s time to learn from communities that have experienced internal migration around the world to prepare our communities for a future migration of households away from the front lines of vulnerable flood plains, seismic zones and fire communities into “higher ground” areas. We must ensure cities have sufficient supplies of backup energy, potable water, affordable and healthy housing, and adequate healthcare and educational services. Supporting receiving communities is as fundamental as supporting vulnerable communities. Many households, like my grandparents, will move to larger anchor cities, that already have core communities to help bridge them into the community.

Households Fleeing Houston following Hurricane Harvey 2017

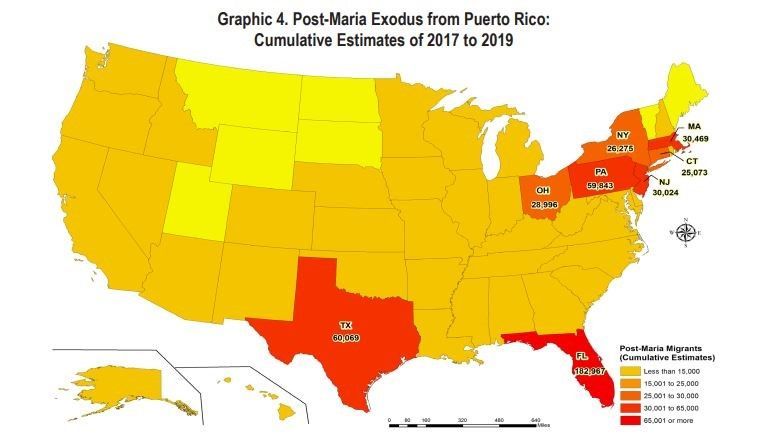

Figure 3 Source: El Centro For Puerto Rican Studies HUNTER 2017 City University of New York's Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College estimates nearly 136,000 Puerto Ricans have relocated to the U.S. after Hurricane Maria. Florida saw the largest influx of people with 56,477, followed by Massachusetts with 15,208, Connecticut with 13,292 and New York with 11,217

People who have been victimized by climate change should be met with compassionate, coordinated support. Here are just a few tenets public sector leadership should keep in mind:

1. Create a sufficient supply of housing and services. The world has witnessed the development of temporary refugee shelter camps that have arisen to meet the immediate shelter needs of individuals and families fleeing war, floods, and other shocks. Housing, food, and medical care essential ingredients for a household to survive yet, thousands of existing US communities lack sufficient affordable housing. Close to 7 million units of affordable housing are needed to provide for extremely low-income households4 and millions more households are overburdened by unaffordable cost of rent. Meeting the basic needs of existing community members let alone newcomers, is a challenge that needs to be addressed and planned for, particularly cities that are front-line receiver communities. Without a plan to address the shelter needs of incoming households, communities are at significant risk. The Alliance for National and Community Resilience created a standard for communities on the provision of sufficient and safe housing and is a good standard to reference: Housing Benchmark - ANCR.

2. Fortify networks of existing ethnic communities. One of the most prominent features of successful integration of immigrant communities across the nation is the presence of a multigenerational “hub” to welcome and establish incoming families and households. Support ethnic and cultural associations--from sport associations to faith-based organizations--that can in turn support newcomers.

3. Invest in the third sector to provide services to communities on the ground. NGOs, first responders, and community-based organizations have always stepped forward to address crises, fill gaps in services and support the most vulnerable in times of strife. However, a considerable challenge is that often these services are delivered for free, with little more than grit and incredible human generosity. This needs to change. Funding needs to be dedicated to supporting the front-line NGO’s and service providers as well as tactical support such as equipment and access to resources and materials to support service provision.

4. Create small business development opportunities. Immigrants drive the engine of production and the building blocks of our economy through creativity, ingenuity, and grit. For example 48% of NYC’s small businesses are run by immigrants, and roughly 26% of New Yorkers work at a small business5. When small businesses vanish, so do jobs, community spaces, and affordable goods and services.

5. Normalize the transition for incoming and existing community members. Newcomer transition into ‘mainstream’ services—such as those provided by employment agencies, municipal social services, or community-based welfare institutions—is an important step in successful resettlement. Language and cultural barriers may contribute to an environment in which both immigrants and longer-term residents feel some level of discomfort with each other. Methods for promoting meaningful contact among community members are critical to build the foundation for a more welcoming community.

6. Learn from precedent and experience of other nations. Encouraging development of peer groups to share learned lessons about integration of newcomers can help expedite solutions to inform policies and programs for newcomers for integration, services, and housing needs. For example, in 2015 a Transatlantic Exchange (WCTE) program was created to connect German cities with US cities to share practices in refugee and immigrant integration and in engaging receiving communities, which were often apprehensive of newcomers. The WCTE brought together cohorts from nine US and German communities to explore innovative approaches to local integration initiatives and covered topics including affordable housing, job training and placement, school integration, language learning, interfaith dialogue, and broader social and cultural integration. The connections formed during this exchange have been used to inform public sector programs and policy in the US and in Germany6.

7. Receiving Communities needs to be supported at Regional and National level. States and Cities need adequate national support to provide integration services and cannot bear the burden alone. The COVID-19 pandemic has erased years of economic gain and revenue from cities and communities across the United States, leaving local governments extremely strapped for funds to cover critical needs of communities. The federal government must partner with localities to ensure there is appropriate resources for communities called to receive incoming residents displaced by a volatile and changing climate.

Over the course of history, humans have adapted to the most unbelievable of circumstances and conditions and become one of the most resilient species on earth. Being forced to leave one’s community is a hardship that even the most robust of us find hard to endure--but collectively, we can ease that transition. As climate risks increase, more people and communities will relocate to find opportunity and safe ground. Our work is to ensure they are received in a strategic and supportive way. In the words of Senator Paul Wellstone “We all do better, when we all do better.”

1. Refugee Crisis in Europe: Aid, Statistics and News | USA for UNHCR (unrefugees.org)

3. Taking India’s Climate Migrants Seriously – The Diplomat

5. United for Small Business NYC | Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (anhd.org)