This year marks the 25th anniversary of the passage of the Native American Housing and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA).

Over the past quarter century, this legislation has transformed the landscape of Indian Country as we know it.

Whether you are fighting for more affordable housing or the economic development of rural and tribal lands, you ought not to let this anniversary pass unnoticed. Let’s reflect on the past 25 years of Indian housing and self-determination and look towards the potential of the next generation.

History of Native Housing

The condition of the housing market on Native American lands before NAHASDA was often inadequate, underdeveloped and unsafe.

This was partially driven by the limits of trust land. For the off-reservation housing market, land is bought and sold in a free market, giving that private market the space to address demand for housing.

As a result of the general allotment act and various court decisions, the federal government in the United States holds reservation lands in trust for the tribe. To this day this creates issues and banks are reluctant to lend, while tribes may not be able to tackle all the necessary steps to build housing.

However, this imperfect system means that tribal land remains in the ownership of tribe, an important element of tribal sovereignty.

The Housing Act of 1937 was one of several smaller programs aimed at tackling housing that could be used on Indian land pre-1996. Neighborhoods of sub-standard homes, built from the same blueprint as thousands of other homes across the country, landscaped the reservations of the late 20th century.

These houses left little connection to traditional ways of life, a far step from the pueblo homes of the southwest or longhouses of the pacific northwest, which were not only culturally significant but climate specific.

Additionally, the tangled regulations and programs that tribes could use each had different requirements, making it difficult to access assistance.

NAHASDA was signed by President Clinton in 1996, and it consolidated pre-existing legislation into two main programs: the Indian Housing Block Grant and Title VI loan guarantee.i

A third element of this legislation was perhaps the most important, and its in the title: self-determination. As NAHASDA was originally envisioned, it would recognize tribal sovereignty or self-determination and even enhance tribal capacity through its housing assistance.

Native American families who receive assistance under NAHASDA must be considered low-income (80% AMI) and reside on the reservation or tribal land.

Building Homes and Improving Capacity

This one piece of legislation has a legacy that can be seen across Indian Country. Since 1996, tribes developed an estimated 40,000 homeownership and 25,000 rental homes for families with low incomes in their community.

HUD funding through NAHASDA can be leveraged to fill the gap in other affordable housing projects, contributing to an estimated 19,000 existing homeownership and 4,000 rental homes acquired for use.

NAHASDA also provides flexibility to smaller tribes who may not have the capacity to take on new development or acquisition, which supports an estimated 137,000 homeownership units and 26,400 rental units rehabilitated in the last 25 years.ii

NAHASDA put Native American tribes on the same level as states: Each year, they submit an Indian Housing Plan similar to a Qualified Action Plan that Pennsylvania or Arizona would have to submit to the federal government.

And just like those states, tribes get the freedom to choose the priorities for their own constituents, which honors the sovereignty of tribal nations while also by-passing some regulatory burdens.

This is a popular approach among tribes: the act went into effect in 1997, and by 1998, 97 percent of tribally designated housing entities had submitted their required housing plan to HUD.iii

In a GAO study in 2015, around 90% of tribal respondents surveyed viewed the effectiveness of NAHASDA as either very positive or somewhat positive, emphasizing the recognition of tribal sovereignty inherit in the program.iv Opinions of NAHASDA in the Native housing industry today remain positive.

Since this legislation’s passage, Native American housing has continued to evolve. NAHASDA was amended in 2000 to include Hawaiian Home Lands, adding Title VIII-Housing Assistance for Native Hawaiians, and the associated Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant (NHHBG).v

The Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Homeownership, or HEARTH Act, was passed in 2012 to help cut through the red tape of BIA approval for land leases. The act opens many benefits such as streamlined processes for residential leases, building on existing tribal capacity.

Native Housing Needs Remain

NAHASDA exists to support the needs of low-, very low-, and extremely low-income Native American households, needs that persist today. Households headed by Native Americans are more likely to be extremely low-income—18% more likely than white households. vi

In addition, as well as facing the rising cost burden of housing across the country,vii housing on Native lands must overcome infrastructure barriers. Native Americans are 19 times more likely than the rest of the population to live without indoor plumbing.viii

In 2017, 88% of tribal housing officials reported homelessness was a problem in their community—not to mention the number of individuals staying in overcrowded conditions.ix

Tribes today are still struggling to meet the demand for housing in their communities, end homelessness, and build a ladder towards wealth through homeownership.

These conditions are likely to have worsened during the pandemic. The Native American unemployment rate—historically 4-5 percentage points above the average—may have grown as much as 10% during the Covid-19 crisis.x

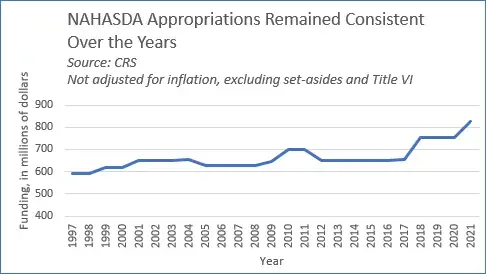

Appropriations for the Native American Housing Block Grant have not kept up with the need in Indian Country, remaining relatively stagnant in much of the last two decades (see graph). In the first year the act was in effect, Congress appropriated $592 million for the Native American Housing Block Grant.

Funding levels rose and then leveled out, averaging $628 from 1997 to 2005. However, in the next decade support for NAHASDA remained at $653 million per year, despite inflation rising during this period.xi

In 2015, the $650 million set aside for the program would have been worth $480 million in 2000, a year when NAHASDA was funded at $620 million.xii

The horizon of funding is looking more hopeful for the tribes and Native families that rely on NAHASDA, with Congress raising the FY 2021 appropriations for the Native American Housing Block Grant to $825 million.

This is the largest nominal amount of funding the program has received, although previous years adjusted for inflation would still be worth more—for example, to match the $620 million in 2000, Congress would award over 1 trillion today.xiii

After 25 years and thousands of Native families served, this successful program deserves more from our representatives.

Reauthorize NAHASDA for Future Generations

Support for the program is not just important at the funding level—Congress also let authorization of the original NAHASDA bill to expire in 2013.

After eight years without official authorization, on September 15, 2021, a recent bill to reauthorize NAHASDA (H.R. 5195) moved from the House Financial Services Committee to by passed by the full House.

This represents a critical opportunity to support homeownership, multifamily rental, housing counseling, loan guarantee—and many other programs for Native American, Alaskan Native, and Hawaiian Native families and tribes.

We know NAHASDA works for low-income Native families. Thank you to all the advocates who have made this legislation possible. Congratulations to all the tribes fighting hard to be awarded and serve their communities every year.

Let’s continue the support of Native American Housing and Self-Determination for the next 25 years and beyond.

Evelyn Immonen is a Program Officer for Enterprise Community Partner’s Rural and Native American Programs, where she supports homeownership and rental programs for tribes and rural housing organizations across the nation. She has three years of experience in research, advocacy, and program management in rural and tribal community development. Her family is from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, and she maintains a connection to many tribes in North and South Dakota.

i https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/ih/codetalk/n…

ii Estimates represents Enterprise’s calculations based on a 2013 GAO report, during 5 year period—production held constant during other 20 years of program: “During fiscal years 2003 through 2008, NAHASDA grantees collectively used IHBG funds to build 8,130 homeownership and 5,011 rental units; acquire 3,811 homeownership and 800 rental units; and rehabilitate 27,422 homeownership and 5,289 rental units https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-10-326.pdf

iii https://www.gao.gov/assets/rced-99-16.pdf

iv https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-10-326.pdf

v https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/ih/codetalk/nahasda

vi https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/2021/Out-of-Reach_2021.pdf

vii https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/2021/Out-of-Reach_2021.pdf

viii From a report using 2015 data: 2014 was the last year the ACS collected data on households with access to a flushing toilet.

ix https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/homelessness-indian-country-hidden-critical-problem

xi Average appropriation per year from Enterprise’s own calculations, based on CRS data

xii Value relative to inflation from Enterprise’s own calculations, based on BLS data

xiii Value relative to inflation from Enterprise’s own calculations, based on BLS data